I went to a Jackson Browne concert with a group of friends a week ago. Yes, he’s still going strong at 60. It was a great show. He played a sufficient number of his hits, like Doctor My Eyes and Running on Empty. For me, the highlight of the night was a very cool version of one of my personal favorites, “Lives in the Balance.” Like many week-old experiences, I can sit back and still visualize a few of the key moments. At the same time, like many week-old experiences, I can feel the memories fading. It’s not that I’m getting old (even though I am); it’s just how memory works.

There is no experience without memory

Aside from whatever you happen to be doing at this precise moment in time, all of your experiences exist only as memories. It is, therefore, impossible to really understand the nature of experience without understanding how we remember those experiences. In this post, I’d like to cover some of the ways that memory affects how we experience the world. This is very important for two reasons:

- One of the least effective ways to understand what someone has experienced is to ask them to tell you about it after the fact. People’s memories of their experiences are notoriously unreliable. The implications of this are significant. For instance, it creates a substantial limitation on how effective simple voice of the customer approaches are for understanding customers’ experiences.

- If you want to design memorable experiences for your customers, you need to understand three things about how memory works: how and why people pay attention to certain features of their experience, how those features and the overall gist of the experience are encoded in memory, and how those memories are recalled. As you will see, understanding these three things is critically important to designing experiences that are much more memorable and, ultimately, much more influential.

Before jumping into this, I’d like to borrow an interesting illustration that Harvard Psychologist, Daniel Gilbert included in his wonderful book, “Stumbling on Happiness.” Look at the six royal cards below and pick one. No, no… don’t tell me which card you picked! Just make sure you remember it. You might want to repeat it to yourself a couple of times or even write it down to make sure you don’t forget.

Okay good! Now that you have your card memorized, I’d like to jump into how memory influences experiences. We’ll see how well you did at remembering the card towards the end of this post.

“Memory is an internal rumor.” George Santayana

Our memories of past experiences are notoriously unreliable. There are three factors that contribute to the problem: 1) limitations in how much we can pay attention to at any moment in time, 2) issues with the way information in short-term memory are encoded into long-term memory, and 3) issues with how memories that we do encode are eventually recalled. Understanding each of these factors provides insight into how to design much more memorable experiences. Let’s take a look at all three.

ATTENTION

Every second, every day, every year, our senses take in millions of bits of rich detail about our experiences… all of the sights, sounds, textures, smells, tastes, etc… However, we only have a limited capacity to attend to all that information. Our conscious stream of the thought relies on short-term memory. This short-term memory provides capacity for holding a small amount of this rich information in an active, readily available state for a short period of time. The duration of short-term memory is about 20 seconds and experiments demonstrate that its capacity ranges from about 3 or 4 elements (i.e., words, digits, or letters) to about 9 elements.

Experiences like a concert, a fine meal, a glass of wine, a movie, browsing through a store, or walking along the street are very complex, rich, and multidimensional. While it’s possible to hold some of that rich detail in short-term memory, it’s not easily translated to long-term memory. We use language or a sort of mentalese in order to extract what seems like the most salient features of our experiences in order to be able to think about them or communicate them later. As a result, the morning after a concert, you only really remember which songs were played, a few features of the way they were played, and the sense about what you liked or disliked about them.

The transfer from short-term to long-term memory involves fast forgetting. There are numerous example of this. For the sake of illustration, suppose I had you memorize a sequence of three letters and then count backwards in groups of three numbers. In experiments to this effect, after counting backwards for 6 seconds, most people only remember about 50% of the letters. After 12 seconds, most people only remember about 15% of the letters.

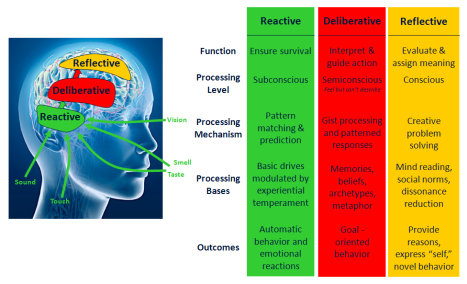

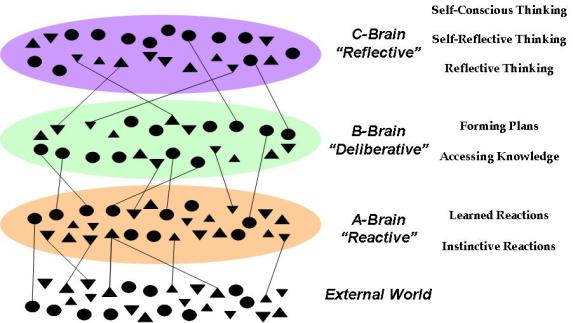

The way we experience the world starts with a combination of selective attention supported by subconscious “gist processing.” We generally pay attention to those elements of our experience that seem most important; the elements that capture our attention because they we were looking forward to them or they stood out because they were particularly high-contrast or they caught us by surprise in some way. Beyond the relatively small amount of information that we’re able to pay conscious attention to; we do something called “gist processing.” Gist processing enables us to get a sense for what is unfolding around us without having to focus attention on all the details. It operates through subconscious pattern matching. We get the gist of what’s happening because it roughly matches experiences we’ve had in the past.

Gorillas, Doors, and Selective Attention

Research provides many interesting examples of selective attention and inattentional blindness. In one of the most striking and well- known demonstrations of selective attention, participants watch a video of people passing a basketball between each other, and they are asked to count the number of passes. As the participants are busy counting the passes, less than 50% of those participants notice that a person dressed in a gorilla suit walks right through the middle of the action, stops, turns, looks at the camera, and does a little dance before turning and walking off the scene. You can see an example of this experiment in one of Michael Shermer’s lectures posted here.

Another well-known example is the ‘door study’. In this experiment, pedestrians are stopped by a researcher who asks them for directions. While the pedestrian is talking to the experimenter, two men carrying a door walk between the two. Hiding behind the door is another experimenter who changes places with the first experimenter. The second experimenter then continues the conversation with the pedestrian. The two experimenters are purposely different in height, weight, coloring, dress, etc… Shockingly, only about half of the pedestrians realized that they were now talking to someone completely different than the person they were talking to at the beginning of the conversation with. I’m sure you’ve had similar experiences? How many of times have you placed an order in a restaurant and not been able to remember who your waitress was five minutes later? These are illustrations of a specific type of inattentional blindness called change blindness. (Click here for some further examples).

So much for our powers of observation! In both examples, the subjects were paying attention to the central aspect of the experience: counting the passes or giving directions. In both examples, subjects were also surprisingly unaware of very significant elements of their experience. If you look at this from the standpoint of evolutionary psychology, it makes total sense. Over history, our survival has been based on recognizing and paying keen attention to those elements of our environment that seem most important while filtering out and not getting distracted by large amounts extraneous detail.

There are serious implications for anyone trying to improve the experience their customers have with their business. It’s very easy to waste a lot of time and money designing experience elements that customers just filter out because those elements are neither central to the goals they are trying to accomplish nor occur on the attentional pathway customers are following in order to accomplish those goals. We’ve found that the subtle elements of experience need to be designed in a way that specifically takes into account how people do gist processing. That is, just give people the cues that will enable them to identify the experience. The worst thing you can do is design a set of experience elements that get the customers’ attention but don’t fit with the way they think… elements that ultimately cause the experience to be both distracting and confusing for the customer.

ENCODING

The second issue has to do with how what we experience gets encoded in long-term memory. We obviously don’t ultimately remember everything that was available to us in short-term memory as we were having the experience. If we did, we’d need a brain many times larger than our current brain. So, essentially, our experiences are compressed for storage. As these experiences are coded in long-term memory, we store a summary of the gist of what happened, tagged with information about how the experience made us feel, along with a small set of specific representations of key features. This is what I have left in my week-old memory of the Jackson Browne concert.

How information is moved into long term memory depends on the depth with which we process information. A classic experiment by Craik and Tulving (1975), tested the strength of memory traces created using three different levels of processing:

- Shallow processing: Participants were shown a word and asked to think about the font it was written in. In other words, they paid attention to peripheral cues rather than the core element of their experience.

- Intermediate processing: Participants were shown a word and asked to think about what it rhymes with. In other words, participants were asked to make an association between their current experience and other experience.

- Deep processing: Participants were shown a word and asked to think about how it would fit into a sentence, or which category of ‘thing’ it was. In this case, participants were asked to directly interact with the core element of the experience… rather than just paying attention to associations or peripheral cues.

Not surprisingly, participants who had encoded the information most deeply remembered the most words when given a surprise test later. But it also took them longer to encode the information in the first place.

Encoding Favors High Contrast, Discrete Features

The most important factor with memory encoding is that our brain does a relatively poor job of encoding rich continuous features (e.g., the way the store looked, the way the music sounded, how the food tasted, how long we waited, etc…) and are somewhat better at remembering high-contrast discrete features (e.g., whether something happened or not, what we ordered at the restaurant, the description we provided after we had the experience, etc…).

The implications of this for experience design are profound and counter-intuitive. Many companies think about the quality of the experience their customers have in terms of a relatively large number of service levels (e.g., how long the customer had to wait for service) or subtle improvements in rich peripheral cues (e.g., store or web design). In most cases, these improvements represent differences in degree that, even if the customer paid attention to them, would only get perceived as “better sameness.” As important as these things seem to be to the company, the typical customer doesn’t encode their experience in a way that makes these things memorable. As discussed earlier, these continuous variables are only important to the extent that they influence the way customers do gist processing.

We’ve found that the most memorable experiences are designed around a small number of high contrast “signature elements.” These signature elements are the things that get the customers’ attention because they “differences in kind” rather than “differences in degree.” Customer service is generally a difference in degree; everyone provides some level of customer service. A specific service that is provided differently than a competitor or differently than the customer expected is a “difference in kind.” For example, experiences at both Starbucks and Caribou coffee shops are built around differences in kind compared to other coffee shops. There are also many specific examples, like the Renaissance Inn in Tulsa which has a totally different design for their front desk area. This hotel has individual reception desks rather than placing a long counter between customers and the front desk clerks… like virtually every other hotel does. As a result, out of all the hotels I’ve stayed at in the past year, this experience was memorable because it included this high contrast “signature element.”

Focusing on designing high-contrast signature elements rather than better sameness peripheral cues is a good start. However, our memories of even the highest contrast elements of our experiences are suspect.

Encoding False Memories

“Most people, probably, are in doubt about certain matters ascribed to their past. They may have seen them, may have said them, done them, or they may only have dreamed or imagined they did so.” William James

As this quote illustrates, another very significant issue related to encoding is misattribution, bias, and the formation of false memories. These encoding issues can have dramatic consequences. For example, Gary Wells and his colleagues at Iowa State University did a study of 40 different miscarriages of justice that relied on inaccurate eye-witness testimony. Many of these falsely convicted people served years in prison; some facing the death penalty.

While memory encoding errors can have disastrous consequences like this, it happens to all of us in less dramatic situations every day. Encoding errors are a regular occurrence for most people. These include:

- Misattributing sources. This includes things such as thinking that you read something in the newspaper when, in reality, a friend told you. It also includes unintentionally thinking you came up with an idea that, in fact, a colleague suggested to you several days earlier. (By the way, I apologize to my very forgiving colleagues for all the times this happens.)

- Mixing memories. There are a very wide range of ways that this happens. For example, you might think you knew something about a product you bought when, in fact, you learned about it after you made the purchase. It’s very common to add new information to memories after the fact.

- Confusing imagined elements of an experience with reality. There are numerous experiments that point to the fact that people often imagine elements of their experiences and create memories of those elements when, in reality, those elements didn’t actually happen. For example, I was talking with someone about how much I enjoyed Jackson Browne’s rendition of the song Load Out. I had been really looking forward to hearing him do it. The issue was, when I checked the set list that was posted online, he didn’t actually performance that song that night. (See also Goff and Roediger, 1998 for other interesting examples of “illusory recollections.)

- Consistency bias. Our memory process is “cognitively conservative.” Our lives are so much simpler if we don’t have to continually re-evaluate what we believe to be true. As a result, we tend to pay attention to and remember the information that conforms to our expectations or justifies our beliefs… while disregarding any information that contradicts those expectations or beliefs. This is an enormous factor in areas of our lives like our personal relationships or our political beliefs. Consistency bias is just one of the many biases that affect our memories.

All of these relatively simple misattributions at least have some basis in reality. They just involve getting a little mixed up on the details. However, we also create entirely false memories. As William James pointed out, memories can be constructed from our realities, our imaginations, and our dreams. For more information on this, I’d suggest checking out C. J. Brainerd and V. F. Reyna‘s book “The Science of False Memory.”

Why All These Idiosyncrasies of Memory are Actually Helpful

Given all of the challenges illustrated above, you might think it’s amazing we can function effectively at all. While these limitations can have a disastrous effect in certain situations, we seem to function pretty well most of the time. It turns out that selective attention, gist processing, and limited memory encoding is a blessing. It spares us from cluttering our minds with a massive amount of meaningless detail. There is a positive correlation between our ability to extract and remember features of our experiences while forgetting the details and our ability to engage in abstract thought and learn from our experiences.

Consider the case of Russian journalist Solomon Shereshevskii, whose memory was so perfect he could remember everything that was ever said to him. Shereshevskii became famous after being criticized for not taking notes while attending a speech in the mid-’20s. To the astonishment of everyone there (and to his own also, due to his belief that everybody could remember that level of detail), he demonstrated his ability to recall the speech perfectly, word by word. There seemed to be no limited to his detailed memory. However, Shereskevkii’s gift had a very significant downside. It was difficult to ignore even the most insignificant events. He remembered every scene, word, cough, scratch, sneeze, meal, etc… In addition, all of these memories were so detailed that it was difficult for him to generalize across experiences or think in the abstract. Shereshevskii was so tortured with the accumulation of memories over time that he had to work out ways to try to intentionally forget.

RECALL

As much as it seems like we retrieve memories from storage, this is actually a very elegant illusion. When we remember past experiences, what we actually do is quickly reconstruct and re-imagine the events by filling in around the relatively small number of features we stored. This whole approach is efficient because it allows us to store a large number of memories. However, it makes the memories we do have highly suspect. It happens so quickly and easily that we get the illusion we are actually remembering what happened while our accounts of those past experiences can be pretty inaccurate.

But our memories seem so real! Memories of past experiences seem real because many of the same portions of the brain are activated when we remember as when we perceived the event in the first place. For example, listening to a song on the radio involve an area of the portion of the brain called the auditory cortex. When you sit and remember what a song sounds like, it also activates the auditory cortex. This use of the same area of the brain is a reason why it’s so difficult to remember how one song goes while you’re listening to another song. It’s also why you can remember the song better if you plug your ears in order to eliminate the confusion associated with the same part of the brain trying to process two different experiences at the same time.

When we remember past experiences, it has an influence on what we will remember about that event the next time around… the story gets sharpened and leveled. Information that is inconsistent with the overall storyline or gist we remember is forgotten (leveled) and features that reinforce our beliefs about the experience are emphasized (sharpened). Often new information is introduced after the fact. Aside from the issues with selective attention and limited encoding of memories, this is yet another reason why relying on eye witnesses creates problems in the criminal justice system. The way a person is questioned about their experience can subtly influence what they remember about that experience.

Daniel Gilbert also shared the following example. Volunteers in an experiment were asked to look at a series of slides that showed a red car approaching a yield sign, turning right, and then knocking over a pedestrian. After seeing the slides, some volunteers (the no-question group) were not asked any questions, and the remaining volunteers (the question group) were. The question that the second group of volunteers was asked was: “Did another car pass the red car while it was stopped at the stop sign?” Next, all the volunteers were shown two pictures: one with the red car approaching a yield sign and one with the red car approaching a stop sign. They were asked to point to the picture they had actually seen. More than 90 percent of the volunteers in the no question group correctly pointed to the yield sign. However, 80 percent of the volunteers in the question group incorrectly pointed to the picture of the car approaching the stop sign. Clearly, the question that was asked influenced the volunteers’ memories of their experience.

There are several interesting implications of how memories are changed as they are recalled and reconstructed. Since I got divorced 10 years ago, I have my two wonderful children with me for just the weekends. Since I wanted to make sure that they always remembered the time we had together in the most positive light, we’ve consistently followed a Sunday evening ritual. In the car on their way home, we have a discussion about the weekend and we each share what we thought were our best experiences. It’s difficult to measure the impact that this has, but I know that it’s had an effect on the positive way they remember the special things we’ve done.

In a business application of a similar approach, I had the chance to work with the late Christine Boskoff, who was one of the most successful high-altitude mountain climbers in the world and the owner of a leading outdoor adventure travel company named Mountain Madness. Her question was how to improve word of mouth about Mountain Madness in order to attract new clients. The recommendation I developed with her was that, on the last day of each trip, there should be a final celebration involving a ceremonial round of “storytelling.” In this storytelling ceremony, each participant would have a chance to share the personal story of their adventure, what it meant to them, and what their most positive takeaways were. The act of telling their own story, in addition to listening to the stories of others, has a powerful effect to prime and prepare clients with the “personal legends” they’ll share with others when they get home. In the course of telling and retelling these legendary stories the most compelling aspects are typically “sharpened” while any of the less positive or inconsistent aspects are “leveled” in order to fit with a more compact storyline.

There are a wide range of approaches we’ve used with our clients. For example, is there a way to provide a personalized summary of the experience the customer had as a memento but do it in a way that positively reinforces the differentiated, signature elements of the experience.

Summary of Implications for Experience Design

Over the course of this post, I’ve covered the ways that memory affects our experiences. I’ve also highlighted several of the many ways that you can design and deliver more memorable experiences by understanding how people pay attention, encode memories, and reconstruct those experiences after the fact. Those strategies include: 1) designing for gist processing and not overinvesting in service improvements or subtle cues that customers tend to filter out, 2) focusing on a small number of high-contrast signature elements that capture the customers’ attention, are easy to encode, and all contribute to a storyline that reinforces the brand, and 3) finding ways to enable customers to recall the experiences they’ve had in the most positive light. As always, there is much more to say about all of these topics. Feel free to submit a comment if you have questions or points to add.

OH… I ALMOST FORGOT… BACK TO THE CARDS

I hope you still remember the card you chose. As you’ve been reading this post, I’ve been running a little web-based subroutine that was able to read your mind. Based on the results of that little program, I’ve removed the card that you chose from the lineup. I’ll leave it up to you to figure out how I did this fairly simple trick.

Filed under: Cognitive Ergonomics, customer behavior, Customer Experience, Neuroeconomics | Tagged: change blindness, Customer Experience, daniel gilbert, experience, experience design, eye witness testimony, false memory, gist processing, inattentional blindness, jackson browne, long term memory, memory, memory encoding, mentalese, misattribution, selective attention, short term memory, signature experience, stumbling on happiness, voice of the customer, william james | 1 Comment »